In general, Jacques de Gheyn II is regarded as the most important draughtsman of The Netherlands right after Rembrandt Harmensz. van Rijn (1606-1669). The Antwerp born Jacques De Gheyn II was initially trained by his father who was active as a glass painter, miniaturist and engraver. After the death of his father in 1581 Jacques left for Haarlem where he took apprenticeship to Hendrick Goltzius (1558-1617). After his master left for his Italian sojourn in 1590, De Gheyn II started his own printshop in Amsterdam. He marries Eva Stalpaert van der Wiele in 1595 and the year thereafrer the couple moves to Leiden where Jacques receives his first Royal commission from Prince Maurice of Orange. From 1605 untill his death in 1629 De Gheyn II lived in The Hague where he was member of the Guild of St. Luke. In The Hague he would receive multiple Royal commissions from the House of Orange-Nassau, of which perhaps the design for the garden of the Prince's garden of the Buitenhof is best remembered.[1][2][3]

De Gheyn's oeuvre consists of a wide array of subjects depicting graphically painstakingly rendered drawings of animals and figures with meticuously detailed facial expressions, the famous series of 117 engravings of soldiers depicting the handling of shutguns ("Wapenhandelinghe van Roers Musquetten ende Spiessen", The Exercise of Arms), allegorical subjects, animals, flowers, solitary studies of trees, vegetation studies and landscape drawings. One of the richest and best preserved collections of drawings by Jacques De Gheyn II is the volume preserved at Fondation Custodia/Coll. Frits Lugt, Paris of small animals, flowers and insects on vellum which previously belonged to Rudolf II of Habsburg, Holy Emperor of Prague.[4][5]

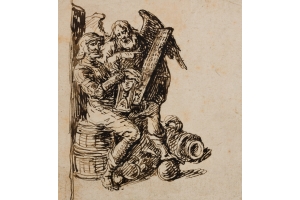

Our set of two calligraph drawings of exactly identical size might have been part of a larger group of allegorical drawings. The very loose handling of the quill by itself dates both sheets beyond doubt as part of De Gheyn's late work, and the date on Father Time's calandar even makes it possible to date it very precisely. The left sheet shows a disillusioned knight, seated on a barrel holding a sandhour while his left foot seeks comfort on a cannonball, staring away after the winged Father Time has shown him his time has come, pointing out at the calendar he holds which reads 1616 and a fragmentary 1617 as the latest dates visible. Father Time's finger points at the year of 1614, but his gesture may also be regarded as a general pointing out, so it's most safe to date the drawing between 1614 and 1616. This drawing may also be interpreted as a so-called "Memento Mori" (remind to die) which was a popular iconographical motif in these days. One of the earliest paintings by Jacques De Gheyn II is his "Vanitas still life" of 1603, to make the spectator aware of the transience of life in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.[6]

Signed and dated drawings are far from uncommon within De Gheyn's oeuvre, though as far as we have traced, aside from "Still-life composed of a book, glass and a cube-shaped box resting on its cover, and the bust of a man with long hair seen in profile" (dated 1609 among the lettering in the book) our drawing is the only drawing by Jacques de Gheyn II which carries a date within the subject depicted and even more specifically as an active part of the drawn composition.[7]

The right drawing shows an even more disillusioned knight who has sank down on his knees on the lap of the witch "Invidia" while she eats out her own heart seated on a globe. Invidia or Envy is the witch from Ovid's Metamorphoses, who lived in a cave, feared for her envious nature. Just like in our drawing, Invidia is often depicted with a swarming mass of snakes as hair, saggy breasts with pointy venomous nipples while she is eating her own heart.

Witchcraft and sorcery were a frequently chosen allegorical iconography by De Gheyn II and he drew Invidia eating her own heart out of envy of the good fortune of others, leaving fire, destruction and havoc on her path previously in 1595 or 1596 after which his pupil Zacharias Dolendo (1561-c.1600) engraved the print as the fourth to the series "Vices and Virtues" from a total series of nine. The Latin verses to the prints written by Hugo de Groot (1583-1645). The drawing of a witch, writing with a quill pen is most illustrative as well.[8][9][10]

Invidia was often depicted as the malevolence of witches who were thought to cause infertility, miscarriages, devoured babies and made witches flying potion from the fat of unbaptized infants. Invidia is the personification of one of the seven deadly sins. Ovid describes in his Metamorphoses how Invidia brings destruction by trampling the meadows, polluting cities with her tainting breath and turning people into stone by infusing them with her pitch-black venom.[11]

The interlacing mythology of Witches and Knights has since long been a tradition in Art, Music and Literature dating as early as the Arthurian legend of Parzival and Morgan Le Fay and more recently John Keats' La Belle Dame Sans Merci (1819) which inspired John William Waterhouse for his eponymous painting dated 1893.

One of the most impressive drawings on sorcery by De Gheyn II is the large sheet present in the collection of the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.[12]

Both present allegorical drawings were discovered and for the first time correctly attributed in 2019 and therefore not mentioned in the catalog raisonné on Jacques De Gheyn II by Professor I.Q. van Regteren Altena.

[1] Haagse Schilders in de Gouden Eeuw. Het Hoogsteder Lexicon van alle schilders werkzaam in Den Haag 1600-1700. Waanders Uitgevers, Zwolle, 1998. p. 133-138.

[2] Jacques de Gheyn II als tekenaar (1565-1629). Museum Boijmans-van Beuningen, Rotterdam/National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1985.

[3] J. Richard Judson, The Drawings of Jacob de Gheyn II.

Grossman Publishers New York, 1973.

[4] I.Q. van Regteren Altena, Jacques de Gheyn, Three Generations.

Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, The Hague/Boston/London, 1983.

[5] ibid. Cat. no. 909-930. Fondation Custodia, Paris , inv./cat.nr 5655.

[6] Jacques De Gheyn II, Vanitas Still Life. Oil on wood, 826 x 540 mm.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Inv. no. 1974.1.

[7] I.Q. van Regteren Altena, Jacques de Gheyn, Three Generations.

Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, The Hague/Boston/London, 1983.

Cat. no. 503. Staatliche Graphische Sammlung, Munich. Inv. no. 41045.

[8] ibid. Cat. no. 180. Jacques de Gheyn II, Invidia (c.1596).

Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg, inv/cat.nr. 52329.

[9] Zacharias Dolendo, Invidia. Hollstein Dutch 71.

[10] Jacques de Gheyn II, A study of a witch, writing with a quill pen.

Sotheby's, Amsterdam, 21 and 22 November 1989, lot #6.

[11] Deanna Petherbridge, Witches and wicked bodies. National Galleries of Scotland in association with the British Museum. Edinburgh, 2013.

[12] I.Q. van Regteren Altena, Jacques de Gheyn, Three Generations.

Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, The Hague/Boston/London, 1983.

Cat. no. 523. A Witche's Kitchen. Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. Inv. no. WA1863.169.